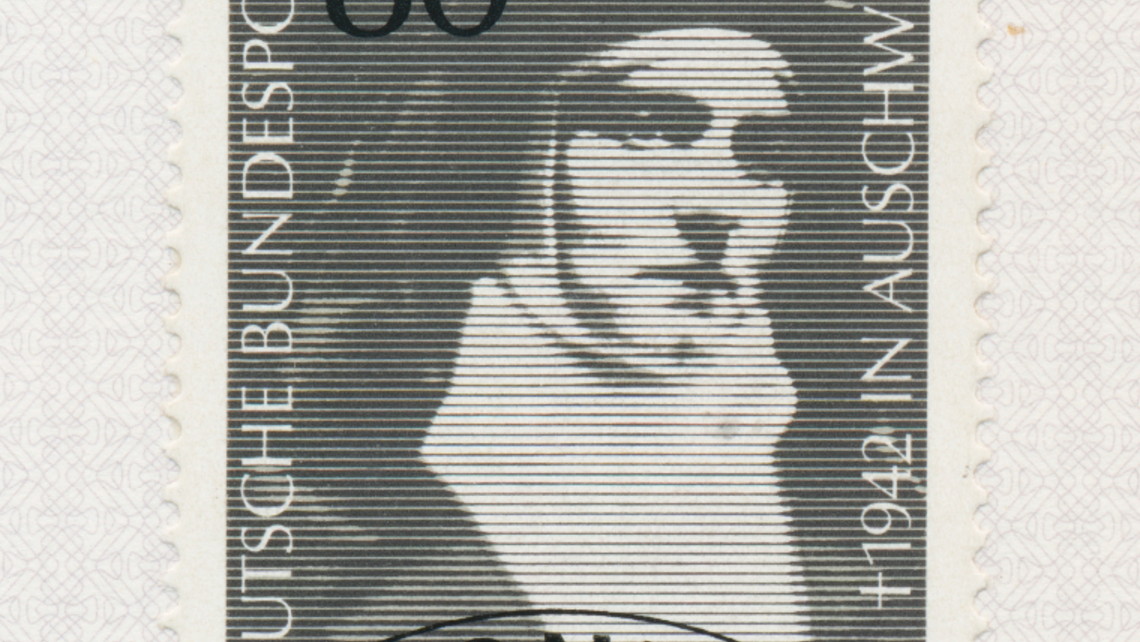

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross’ Story

Edith Stein was born of Jewish parents in 1891, becoming an influential philosopher following her extensive studies at major German universities. After her conversion to Catholicism, she became a major force in German intellectual life, entering the Discalced Carmelites in 1933, and taking the name Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. She was arrested by the Nazi regime in 1942, along with all Catholics of Jewish extraction and transported by cattle train to the death camp of Auschwitz. She died in the gas chambers at Auschwitz that same year.

Born Edith Stein, Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (1891–1942) grew up in a devout Jewish family. Even so, at about the age of fourteen she “consciously and deliberately lost the habit of praying” and ceased believing in God. Even as the divine light faded for her, she sought to replace her childhood faith with a search for truth.

In his canonization homily, Pope Saint John Paul II said, Edith’s “mind never tired of searching and her heart always yearned for hope. She traveled the arduous path of philosophy with passionate enthusiasm.”

Her tremendous intellectual gifts and academic achievements were such that she participated with the great philosopher Edmund Husserl in the beginnings of a new philosophical school called phenomenology. As she herself wrote, “we were repeatedly enjoined to observe all things without prejudice, to discard all possible ‘blinders.’”

And casting off all blinders, Edith’s search was eventually rewarded: “She seized the truth,” said John Paul II. “Or better: she was seized by it.” And when the truth seized her, she “discovered that truth had a name: Jesus Christ. From that moment on, the incarnate Word was her One and All.”

On January 1, 1922, Edith was baptised “Teresa Hedwig,” in honor of Saint Teresa of Avila, whose autobiography had been the final ray in her search for the light of truth. Edith took the Carmelite habit in 1934 and received the religious name, Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

As the Second World War engulfed Europe and the diabolical plan to exterminate the Jewish people pushed forward, the Dutch Church’s outcry against Nazi atrocities resulted in the roundup of all the Catholic Jews in Holland: Sr. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross was targeted for the death camps.

As the Roman Martyrology puts it, “she was forced into captive exile under a wicked regime hostile to human dignity and the faith, and was killed in the gas chamber in the extermination camp of Oświęcim or Auschwitz near Cracow in Poland” on August 9, 1942.

It was love that brought Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross to the point of martyrdom. Indeed, just before the war began she wrote to her superior: “please permit me to offer myself to the Heart of Jesus as a sacrifice of atonement for true peace, that if possible the reign of Antichrist might be broken without another world war and a new social order might be established.”

As Bishop Robert Barron puts it, this woman, “born on the Jewish Day of Atonement, received into the church on the feast day of the first shedding of the Savior’s blood, and given a name in religion designating the blessing of the cross, knew that her life was wound around the mystery of Christ’s redemptive death. With her oblation, she was formally recognising this connection and stating her desire that she might be mystically joined to Jesus’s work of defeating evil through self-immolation in love.”

After she was canonised a saint by Pope Saint John Paul II in 1988, this “martyr for love” was named one of the co-patrons of Europe.

When Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross was finally seized by the Truth, she was simultaneously enveloped in Love. As John Paul II said, for Saint Teresa, the “quest for truth and its expression in love did not seem at odds to her; on the contrary she realized that they call for one another.” Indeed, Truth and Love find their deepest visible expression in the Mystery of the Most Holy Eucharist.

As Saint Teresa wrote, “Whoever is imbued with a lively faith in Christ present in the tabernacle, whoever knows that a friend waits here constantly — always with the time, patience, and sympathy to listen to complaints, petitions, and problems, with counsel and help in all things — this person cannot remain desolate and forsaken even under the greatest difficulties. He always has a refuge where quietude and peace can again be found.”

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross’ love for Our Lord in the Holy Eucharist extended to countless hours in the Lord’s Presence. The following poem is hers:

This Heart, it beats for us in a small tabernacle

Where it remains mysteriously hidden

In that still, white host.

That is your royal throne on earth, O Lord,

Which visibly you have erected for us,

And you are pleased when I approach it.

Full of love, you sink your gaze into mine

And bend your ear to my quiet words

And deeply fill my heart with peace.

Yet your love is not satisfied

With this exchange that could still lead to separation:

Your heart requires more.

You come to me as early morning’s meal each daybreak.

Your flesh and blood become food and drink for me

And something wonderful happens.

Your body mysteriously permeates mine

And your soul unites with mine:

I am no longer what once I was.

You come and go, but the seed

That you sowed for future glory remains behind

Buried in this body of dust.

A luster of heaven remains in the soul,

A deep glow remains in the eyes,

A soaring in the tone of voice.

–St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (1891–1942)

• The above poem is excerpted from Mystery of the Altar: Meditations on the Eucharist, by Kenneth J. Howell & Joseph Crownwood (Emmaus Road Press, 2022).